China’s PISA success—less than meets the eye

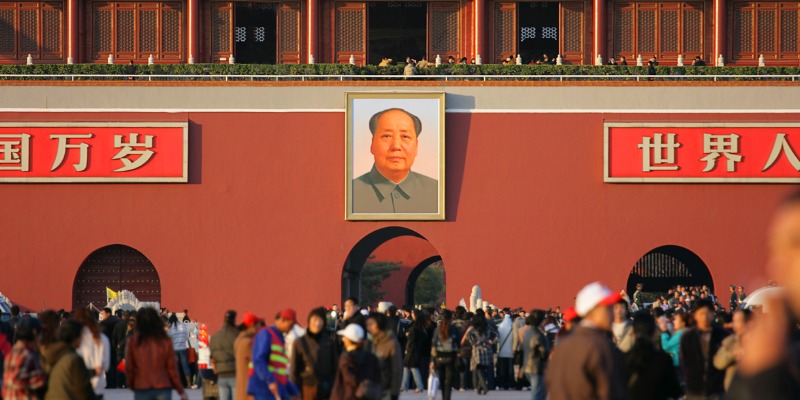

Following Chairman Mao’s lead, Chinese propaganda often referred to America as a Paper Tiger back in the day, implying a lack of substance behind a strong facade.

Although the term hasn’t found much use recently, there’s no lack of apt applications vying for attention. One, ironically, concerns China’s position as the highest-scoring participant in the most recent PISA tests (2018) of international academic performance among 15 year olds. According to PISA, China (BSJZ)—more on that acronym in a moment—dominated the results, with stellar scores in reading, math and science.

Somewhat strangely, Hong Kong (China) and Macao (China) also appear in the list of top-scoring participants. One country with three different national school systems? This is more than odd as the schools in Macao and Hong Kong were operating independently long before they were absorbed by China into “special administrative regions.”

What’s more, it turns out that China (BSJZ) stands for Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, four of the richest and most urbanized of China’s 23 regular provinces. As noted by education researcher Tom Loveless, while the combined BSJZ population of 180 million is larger than all G7 countries (except the United States), it’s only 13 per cent of China’s total population, a large proportion of which lives in undeveloped rural areas with low levels of school enrollment.

In short, as noted in my recent study published by the Fraser Institute, the students tested in China (BSJZ) are not representative of the country as a whole, making China’s PISA results—all three of them!—paper tigers.

Still, results from other countries have aspects of paper tiger-ness to them, although this is typically a case of misinterpretation rather than misrepresentation. Canada is a prime example. While PISA presents our impressive results as representing the whole country, we don’t have a national school system. Instead, the provinces and territories control their schools free of regulation by a national education authority.

However, because PISA draws representative samples of students in each province (the territories are ignored), separate results are available for each, revealing meaningful performance differences. Quebec, for example, substantially outperforms all other provinces in math. Yet this and other provincial-level performance differences disappear in the national results.

Results from the U.S. turn this kind of paper tigerism inside out. In this case, each of the 50 states (and Washington, D.C.) exercise varying degrees of independent control over their schools within overarching policy and funding frameworks imposed by the national Department of Education. Yet PISA doesn’t draw representative samples from each state and the reported results are pooled to represent the U.S. as a whole.

Even so, America’s internal testing reveals substantial variations in the academic performance of different states. Over the last decade, for example, Massachusetts and New Jersey consistently outscored all other states in Grade 4 and Grade 8 reading, with Louisiana, New Mexico and Alaska having the lowest scores by substantial margins.

Comparing the performance of national school systems remains a complex business, which often glosses over important differences. This can create a small menagerie of paper tigers, most of which do little harm other than allowing misinterpretation through oversimplification. The various China tigers, though, are different beasts that should be viewed with caution.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.