Incentives, Identity, and the Growth of Canada's Indigenous Population

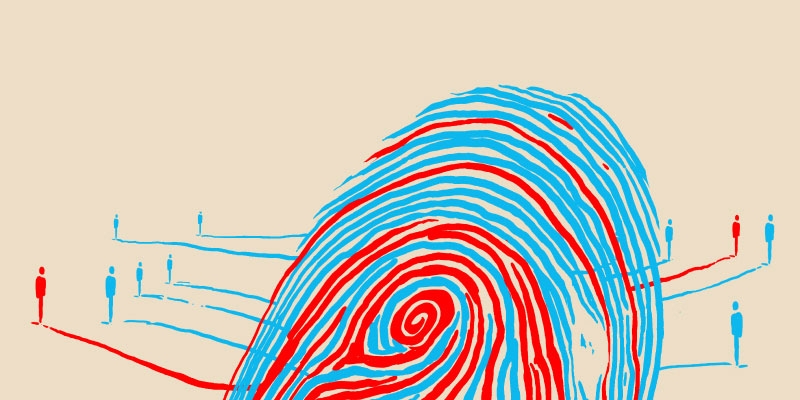

Statistics Canada has reported unprecedented growth in Canada’s Indigenous population (Indian, Métis, and Inuit). Over the 25 years from 1986 to 2011, it grew from 373,265 to 1,400,685, an increase of 275%, while the population of Canada increased by only 32% in the same period of time. Although Canada’s Indigenous peoples have higher birth rates than other Canadian groups, most of this increase resulted from “ethnic mobility”—individuals changing the identity labels they apply to themselves.

By far the greatest growth occurred in the categories of Métis and non-status Indian, which is purely a function of how respondents describe themselves in the census. But the numbers of Registered Indians (a distinct legal status) have also grown much faster than can be accounted for by natural increase. This paper deals with identity issues surrounding Registered Indian status and First Nations membership; a subsequent paper will deal with the Métis.

Ethnic mobility resulting in the growth in the numbers of Registered Indians has been fostered by adoption of equality rights in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982); court decisions such as Lovelace (1981), McIvor (2009), and Gehl (2017); statutes such as Bill C-31 (1985) and Bill C-3 (2011); and the recognition by order-in-council of landless bands such as the Qalipu Mi’kmak First Nation (2011). The Registered Indian population is now at least 40% larger because of these legal changes than it otherwise would have been.

An important factor in the growth of the status Indian population is the set of positive economic incentives conferred by Registration, including free supplementary health insurance for all Registered Indians and Inuit, and in some circumstances financial assistance for higher education, exemption from taxation on reserve, and special wildlife harvesting rights. Such benefits can be substantial and are particularly attractive now that the former legal disabilities connected to Indian status, such as not being able to vote, have been repealed. The medical insurance plan alone is worth about $1,200 per person per year. Though social disadvantages of Indian status may still exist, the legal and economic benefits are now substantial enough to create incentives to seek Registered status.

First Nations were established as distinct political communities; but political, judicial, and administrative trends are combining to confer Registered status upon many people who have some degree of Indian ancestry but are not really part of First Nation communities. Ethnic mobility resulting in growth of the Registered Indian population means upward pressure on federal and provincial budgets, because population counts affect Indigenous programming. But expense is not the only concern; these changes also raise a fundamental question: is it justifiable to offer special government benefits solely on the basis of ancestry?