Canada’s ‘Fiscal Stabilization’ program—what is it, and is it working well?

The Trudeau government recently announced reforms to Canada’s contentious Fiscal Stabilization Program (FSP), which delivers payments to provinces that experience a sharp year-over-year decline in revenue. It’s useful to think of the FSP as a sort of insurance program meant to help provinces cope with unexpected revenue shocks.

The reforms are the first significant change to the FSP in many years. But some argue they don’t go far enough. For example, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney called the changes a “slap in the face” to Alberta because they don’t do enough to help the province during this difficult time.

In this post, we don’t seek to assess the adequacy of the reforms or the reasonableness of Premier Kenney’s characterization, rather we provide a brief description of the program, the main reform and the relevant data to shed light on how this obscure program works, to help Albertans and other Canadians form their own assessments.

Before discussing the primary reform, let’s take a moment to understand the problem it’s meant to solve.

The FSP has come under increased scrutiny in recent years primarily due to fiscal shocks in Alberta against which the program provided very little protection. For instance, after making a small adjustment for changes in tax policy, in 2015/16 Alberta suffered a revenue decline of $7.2 billion from the previous year. The FSP program provided Alberta with just $248 million in relief. This means that the FSP replaced just 3.5 per cent of Alberta’s revenue loss. That’s not much insurance.

The reason that the FSP payments were so small in 2015/16 relative to the size of Alberta’s revenue loss is simple. The formula included a cap that set a maximum $60 per person payment.

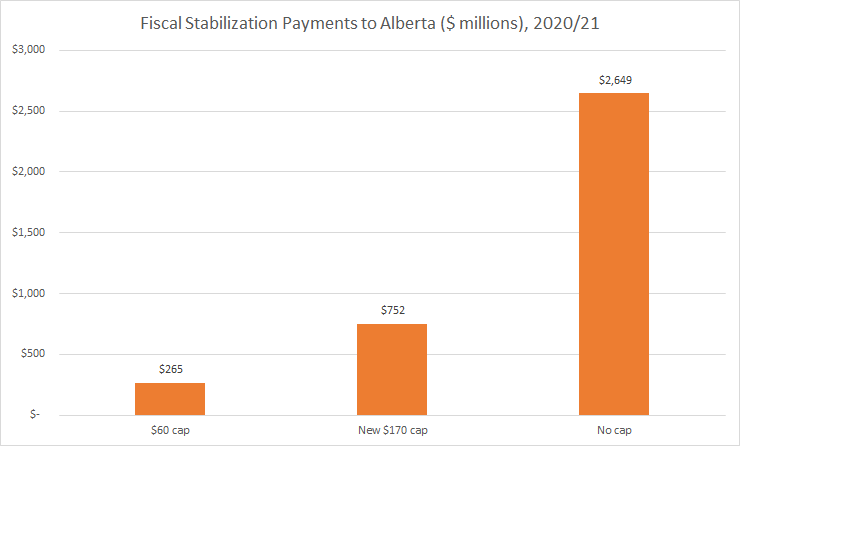

The FSP became news again this year as several provinces suffered significant revenue shocks due to the COVID recession and may become eligible for stabilization payments. Once again (as in 2015/16), under the old $60 per person cap, Alberta would receive only approximately $265 million while suffering significant revenue loss similar to that of the last recession.

The Trudeau government’s reforms announced this week primarily aim to provide additional support to Alberta. There were a few changes, but the most important was raising the cap from $60 per person to $170 per person. This number is based on the original cap that was created in the late 1980s ($60 per person) and indexed economic growth since then. It will continue to grow in line with the rate of economic growth per person. Although the original cap was for the most part arbitrary and so too is the new one, the reform at least reversed the gradual erosion in the real value of the cap, which has occurred through sheer policy neglect due to the effect of inflation.

To be sure, this will result in an increase to Alberta’s stabilization payments this year. Under the old rule, Alberta would have received approximately $265 million. Instead, it will receive nearly three times that amount, at approximately $752 million.

But Alberta politicians of different political stripes argue it’s not enough to protect provinces from adverse fiscal shocks. Alberta Finance Minister Travis Toews, for instance, has argued for the removal of a per-person cap entirely. In the absence of a cap, we estimate the FSP formula would produce approximately $2.6 billion in stabilization payments for Alberta (this is a rough estimate, which we are confident is accurate enough based on currently available data to be useful for illustrative purposes). The chart below visually illustrates these three policy scenarios.

Clearly, the removal of a cap would fundamentally transform the capacity of the FSP to provide “insurance” against a major revenue shock such as Alberta is experiencing today. Under the old $60 per person cap, the stabilization payment would cover just 5.5 per cent of Alberta’s year-over-year revenue loss for 2020/21. Under the new $170 cap, the payment would cover an estimated 15.6 per cent of Alberta’s year-over-year revenue loss. In the absence of any cap, the payment would replace 55.1 per cent of the province’s revenue decline in 2020/21.

The question of whether a fundamentally different FSP capable of providing such a large payment to provinces is complicated. Such large stabilization payments as proposed by Minister Toews would create even worse budgeting incentives surrounding resource revenues than already exist. Specifically, if a resource-rich province knows that it can spend freely during good times because the federal government will cover much of the lost revenue if resource prices fall, the incentives for high spending during good times become even worse than they already are. On the other hand, it’s reasonable to question the utility of an “insurance” program that provides such limited protection.

There may be room for some common ground. The FSP law allows the federal finance minister to provide interest-free loans to provinces that ask for any additional amount beyond the per-person cap they would be eligible for in the cap’s absence. If Alberta makes this request and the federal government accedes to it, it would save the Alberta government some money in interest payments on debt it’s accumulating this year. Given that the federal government can borrow at a lower interest rate than Alberta, extending this offer may be a small token of good faith to help improve relations between Ottawa and Edmonton.

The Trudeau government’s FSP reforms were undertaken primarily with Alberta in mind, and they will provide the province with about $500 million extra in stabilization payments beyond what it would have received under the old rules. Still, the reformed stabilization program will protect Alberta from just 15.5 per cent of the revenue shock it suffered this year. Premier Kenney says the help is so trivial it constitutes a “slap in the face” to Albertans. This post has sought to describe the program, the recent reforms and the relevant data to help readers decide for themselves whether they agree with the premier or not.