Three recessions—a history of Ontario’s debt growth

Observers and analysts of fiscal policy in Ontario are well aware of the province’s large and growing debt.

In 2021/22, nominal provincial government debt will reach a forecasted $439.8 billion. That means the province’s net debt this year will be 48.8 per cent as large as all the goods and services produced in the province this year. This is called the net debt-to-GDP ratio, a key metric economists use to assess the scale of a government’s debt burden. At 48.8 per cent, Ontario’s ratio this year will be the highest in provincial history.

A brief review of Ontario’s fiscal history shows us how we got to this point, and includes lessons the Ford government can consider as we emerge from the COVID-19 recession.

In short, the growth of Ontario’s debt pre-COVID was a tale of two recessions and government choices during and immediately after those recessions. In 1990, Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio stood at just 13.4 per cent. In the early-1990s Ontario went through a steep recession, which put downward pressure on government revenues. At the same time, the government of Bob Rae increased spending dramatically. As a result, Ontario’s debt burden ballooned. In just a few years, the province’s nominal debt climbed from $38.4 billion in 1990 to $101.9 billion in 1995.

This run-up in debt was not just the result of the recession and spending choices during the recession, but also of choices the provincial government made in subsequent years. The Rae government did not prioritize reducing spending back to pre-recession levels, which meant that debt continued to grow, climbing from 13.4 per cent in 1990 to 30.3 per cent in 1995.

In subsequent years, and particularly during the tenure of Premier Mike Harris, Ontario’s debt burden shrank gradually but never came close to debt levels that prevailed prior to the recession of early-1990s.

In 2008/09, Ontario’s economy was hit by another steep recession and history repeated itself as the provincial government of Premier McGuinty increased spending sharply during the recession and then, under premiers McGuinty and Wynne, did not reduce spending commensurately post-recession, which led to another rapid run-up in debt. This time, provincial debt climbed from 27.8 per cent in 2008-09 to 40.5 per cent in 2014/15 and then hovered close to that level for the remaining pre-covid years of the 2010s.

The recessions of the early-1990s and late-2000s and the policy choices during and after these recessions are the reason for Ontario’s climb from a debt-to-GDP of 13.4 per cent in 1990 to approximately 40 per cent in 2019.

Finally, Ontario’s economy was been rocked by a third severe recession in 2020 due to the pandemic. Provincial debt-to-GDP climbed quickly during the recession, from 39.6 per cent to a projected record of 48.8 per cent. What remains to be seen is whether history will repeat itself and the provincial government will continue to pile up new debt in the years subsequent to the recession or whether it will reduce the annual deficit quickly.

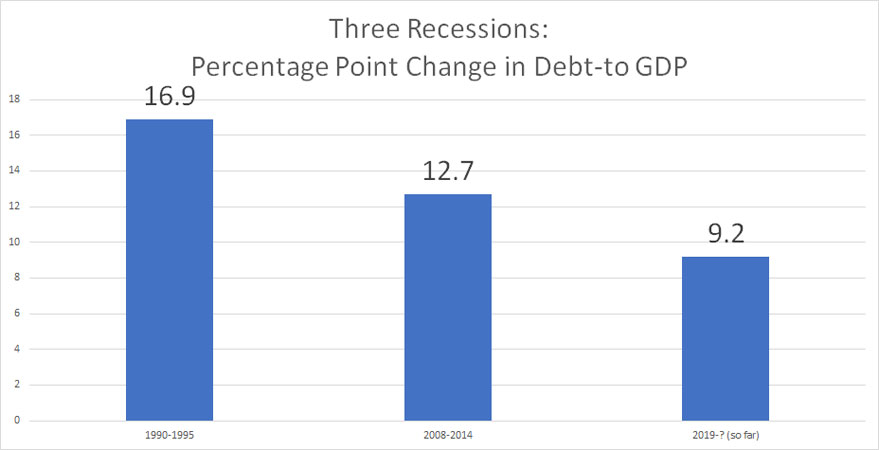

The chart above helps illustrate the data and the challenge ahead for the Ford government or any potential successor. As we’ve seen, Ontario’s debt has climbed from its 1990 level primarily because of developments during and in the wake of three recessions. In the early-1990s, provincial debt climbed by 16.9 percentage points. In the 2008/09 recession and its aftermath, the increase was 12.7 percentage points. So far, the increase in Ontario including this year is forecasted to be 9.2 per centage points.

The history of Ontario’s debt growth since the 1990s is relatively straightforward—two steep recessions and the policy choices made during and after those recessions caused the provincial debt burden to climb. The province has now endured the COVID recession and seen the debt burden climb again relative to the size of the economy. Whether the increase in the province’s debt burden (relative to the size of the economy) will be as large as what occurred under Premier Rae in the 1990s or premiers McGuinty and Wynne in the late-2000s and early-2010s remains to be seen and will depend in large measure on the government’s policy choices in the years ahead.

An even bigger problem is the fact that the province’s debt load relative to the size of its economy is forecasted to keep growing. Analysis from the “Finances of the Nation” project shows that Ontario’s finances are unsustainable, which means that absent policy change Ontario’s debt burden will continue to rise over time. This analysis shows that to make Ontario’s finances sustainable without tax increases the provincial government must reduce spending by the equivalent of 2.5 per cent of GDP.