B.C.’s recent spending spree may soon lead to budget deficits

For more than the first decade and a half of the new century, the British Columbia government was one of the most disciplined spenders in Canada. Since 2017/18, however, and the election of a new government, fiscal policy in the province has taken a decided turn towards big spending.

Let’s start with the period from 1999/2000 to 2016/17. During that time, B.C. held inflation-adjusted per-person spending growth to an average compound annual rate of just 0.5 per cent. As a result, aggregate growth over the entire 17-year period was 8.4 per cent. For comparison, during that same period the Alberta government increased spending by 66.1 per cent.

B.C. wasn’t just disciplined compared to Alberta, but also to the rest of the country. The rest of the provinces taken together, other than Alberta and B.C., saw spending increase by 35.0 per cent. Not as high as Alberta, but still much more than the aggregate increase of 8.4 per cent in B.C.

But again, since the 2017 election we’ve have seen a major policy shift and tilt away from spending discipline. Remember that average annual per-person compound spending growth was 0.5 per cent during the restraint era. Between 2016/17 and 2019/20 (the last year before data become complicated by COVID expenditures), annual spending growth has increased to 4.7 per cent. And that’s after adjusting for changes in population and inflation.

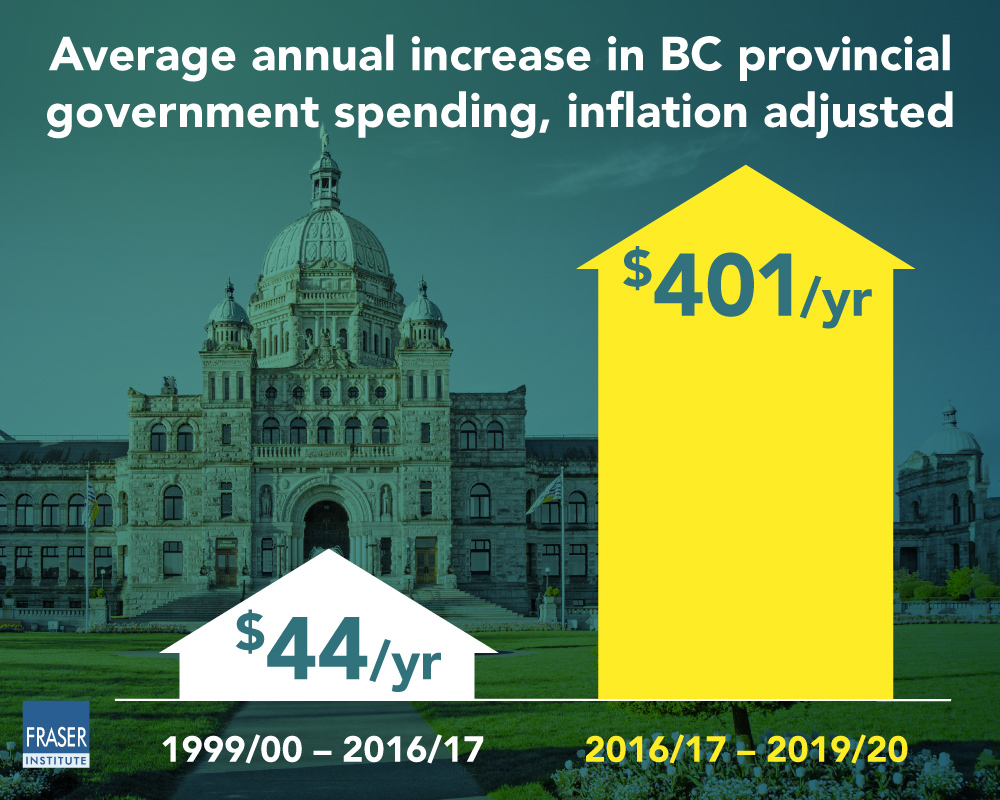

Put differently, during the 17-year restraint period, inflation-adjusted per-person spending increased by $44 per year compared to $401 from 2016/17 to 2019/20.

As a result, spending has increased more in just three years than it did over the entire 17-year restraint era that preceded those three years.

This seismic shift should concern British Columbians. By consistently preventing spending growth from meaningfully outpacing population growth and inflation during the restraint era, successive governments in Victoria helped avoid the substantial run-ups in debt that happened in other provinces including Ontario and Alberta. This has in turn helped limit the amount of taxpayer money needed each year to pay interest on government debt.

If the new approach persists in years ahead, it will almost certainly be impossible to avoid running up debt in B.C. for much longer. The province’s last budget forecast a significant debt run-up over the next few years. This outcome was delayed by an unexpected revenue windfall in 2021, but it’s not reasonable to expect similar revenue growth in future years. If real per-person growth continues to grow as quickly as it did during the immediate post-restraint era, the province will almost certainly return to significant budget deficits and debt accumulation.