Debt interest costs threaten sustainability of federal finances

One of the notable features of the pandemic response in Canada was the enormous amount of federal fiscal stimulus injected into the economy.

Federal spending rose from $363 billion in fiscal year 2019-20 to $639 billion in 2020-21—an increase of 73 per cent. It then began to decline, down to $480 billion as reported in Budget 2023 but is set to resume an upward trend and is expected to reach $556 billion by 2027-28.

As of the 2022-23 fiscal year, federal spending is 37 per cent higher than going into the pandemic, meaning an average annual increase in spending of about 12 per cent. This has been funded by budget deficits, which in turn have increased the federal net debt dramatically from $813 billion in 2019-20 to $1.3 trillion by 2022-23. Ottawa’s debt is expected to eclipse $1.4 trillion by 2027-28.

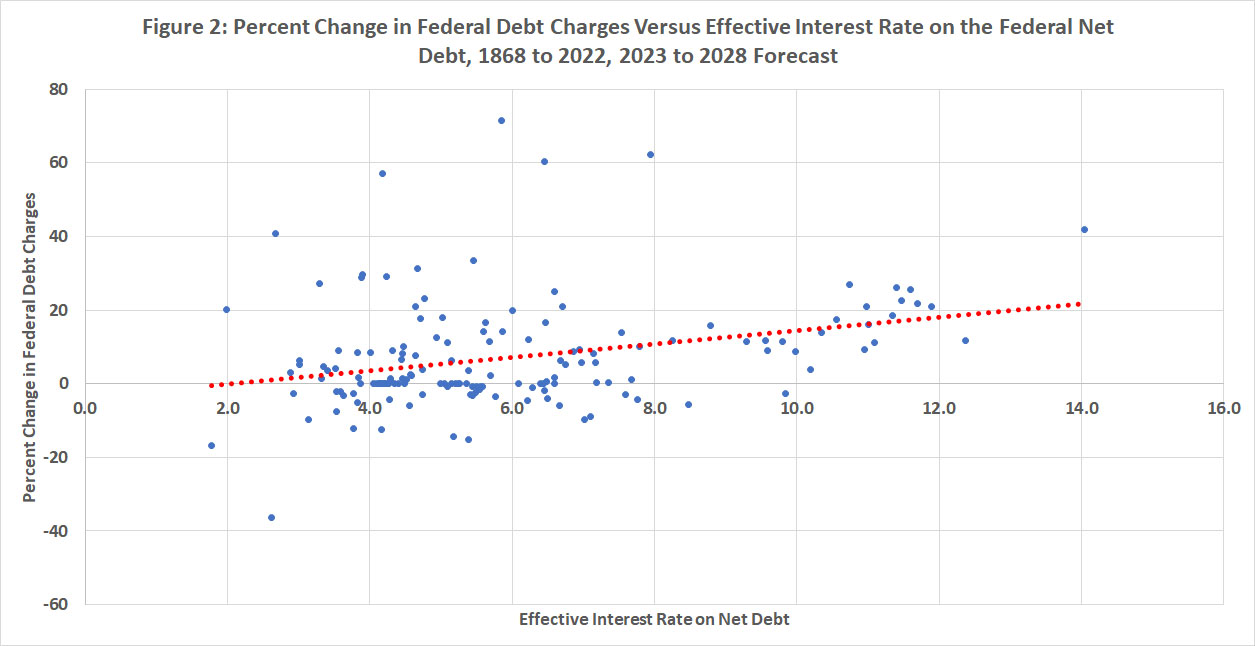

Then there’s debt interest. As a result of recent interest rate increases, debt interest costs are about to become in nominal terms the largest they’ve ever been. Using data from the federal Fiscal Reference Tables and Budget 2023, the first chart below plots both the total annual amount of federal debt charges paid and the annual per cent increase from 2000 to 2022, and then as forecasted until 2028.

Until 2021, annual debt charges had been on a downward trend falling from nearly $44 billion in 2011 to $20.4 billion in 2021. Since then, they’ve soared, growing by 20 per cent in 2022 and forecast at 41 per cent growth in 2023 and 27 per cent growth in 2024. Indeed, by 2028, annual debt interest costs are anticipated under the current forecast to eclipse $50 billion, which surpasses the peaks reached in the 1990s.

Now of course, as a share of total federal government spending, these debt charges may seem less alarming—at less than 10 per cent of total spending, they are modest relative to peaks of nearly 30 per cent or more in the 1990s and 1930s. However, the share of total federal government spending going to debt interest more than doubled between 2021 and 2023, rising from 3.2 per cent to 7.2 per cent, and is expected to keep rising to more than 9 per cent by 2028. Nothing to worry about, you might think, but it all depends on what happens to interest rates. There’s a strong correlation between the growth rate of federal debt charges and the effective interest rate on the net federal debt.

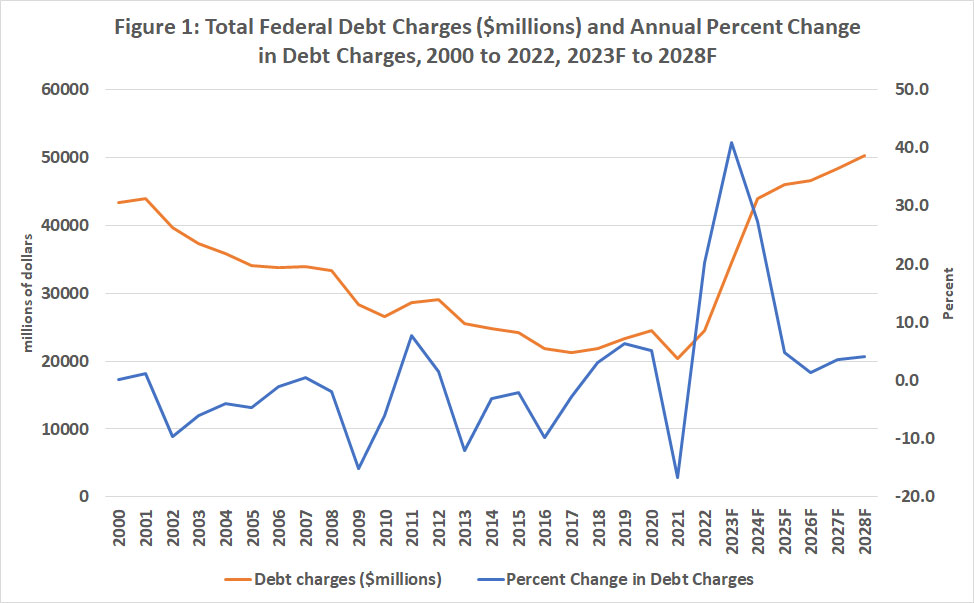

The second chart plots the annual per cent change in federal debt charges against the effective interest rate on the net debt since 1867 (calculated as debt charges divided by net debt) using data from A Federal Fiscal History, the federal Fiscal Reference Tables and Budget 2023.

With a linear trend fitted, there’s a definite positive correlation that has a bigger impact than you might think. On average, a one percentage point increase in the rate of interest is associated with a nearly 2 per cent increase in debt charges. Given such sensitivity, it’s not a surprise that debt charges have doubled since 2021. And the current situation is anything but average given the enormous stock of nominal debt, meaning that even with the staggering of long-term government bond debt issue, small interest rate increases can trigger large increases in government debt interest costs. Moreover, with anemic real GDP growth forecasts and an increase in interest rates, the long-term sustainability of the federal fiscal position becomes more of an issue. We are in for interesting times.