What can Doug Ford learn from Jean Chretien?

Recently, the credit rating agency Fitch lowered Ontario’s credit rating outlook. Specifically, while maintaining the provincial government’s “AA” rating, our outlook was changed from “stable” to “negative,” meaning a downgrade in the future is more likely. If such a downgrade is issued, higher borrowing costs could result.

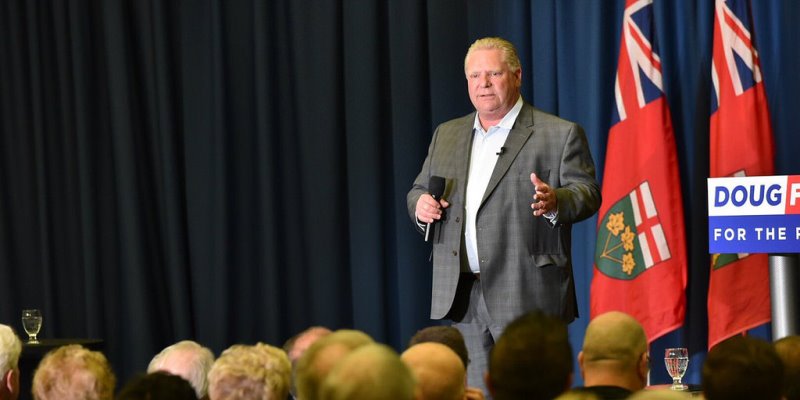

This development underscores the fiscal challenges facing the new Ford government. Indeed, while Premier Doug Ford and his new cabinet face many challenges, the government’s huge debt and substantial deficit are among the most daunting.

Let’s review the numbers. The province’s debt load has more than doubled in nominal terms since 2007 and will reach $325 billion this year. What’s more, the recently-defeated Liberal government tabled a spending plan in the spring forecasting a return to operating deficits and more than $10 billion in new debt annually for the foreseeable future.

How should the new government address these challenges?

First, it must recognize why Ontario is in so much fiscal trouble—unsustainable growth in government spending.

Consider that from 2003/04 to 2015/16, program spending (all spending other than debt interest) grew at an average annual rate of 4.7 per cent—far more than needed to keep pace with inflation and population growth (2.8 per cent). It was also faster than the rate of nominal economic growth (3.2 per cent).

If the government had increased spending more prudently—with spending growth aligned with economic growth, for example—the explosion of new debt in Ontario wouldn’t have happened. Since spending is the problem, the solution must focus on the expenditures side of the ledger. A look at Canadian history shows even substantial deficit and debt problems can be successfully addressed in this manner.

For example, when former prime minister Jean Chretien’s Liberal government faced deficits and credit downgrades in the 1990s, it conducted a comprehensive spending review and tackled the deficit aggressively by focusing on the spending side of the ledger. That government reduced spending by approximately 10 per cent, eliminated the deficit quickly, and repaired federal finances.

Our history shows that this type of fast-moving deficit reduction is often more successful than “slow and steady” approaches based on the notion of holding spending growth relatively low without ever actually making reductions and hoping for revenue to catch up.

Indeed, that’s how the Wynne government in Ontario tried to address Ontario’s deficit over the past half-decade. It slowed spending growth following the 2008/09 recession in an attempt to deal with the deficit. The deficit did slowly shrink—but the province was still in the red year after year, so debt piled up. What’s more, the government wasn’t willing to stick with spending restraint over the long-haul, and cranked up spending growth again in 2017/18 as an election drew near. So the problem never actually got solved.

Clearly, Premier Ford would better serve Ontarians by studying the deficit-reduction efforts of Jean Chretien’s government in the 1990s rather than the failed fiscal strategy of former premier Kathleen Wynne.

For Premier Ford and his new finance minister Victor Fedeli, the task is clear. To address Ontario’s fiscal problems, they must start with a strong understanding of the source of the province’s problems. Addressing Ontario’s spending problem, directly and quickly, is the surest way for the new government to reverse the long-running deterioration of Ontario’s finances.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.