Canada might improve Olympic success by limiting range of sports

After every Olympics, all countries assess the effectiveness of their policies used to train and select the athletes they send to the Games. Such assessment relies mostly on countries’ ranking by some simple metrics.

The most widely used metric is the number of medals won. In Rio, Canada’s team won four gold, three silver and 15 bronze medals, for a total of 22, which finds Canada ranked tenth in the world.

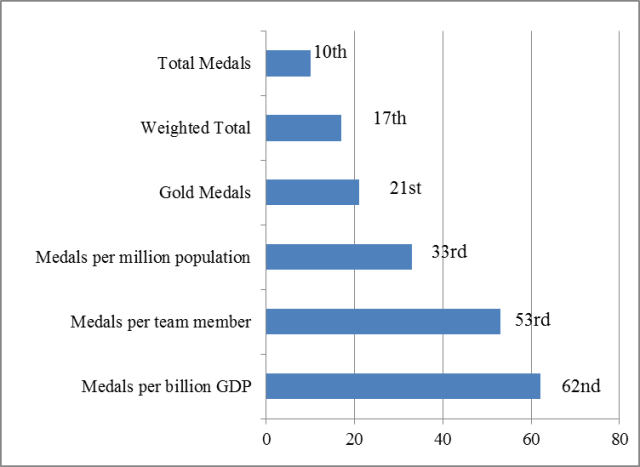

One problem with using the sum of medals as a metric of success, however, is that it counts equally medals of all colours. Ranking on the basis of gold medals alone Canada is in 21st place. Assigning four points for gold, two for silver and one for bronze Canada’s medal count is 37 and brings an excellent place 17. Ranking countries by the number of medals won for every million of people Canada is in 33rd place. According to the count of medals won per billion dollars of national income, Canada ranks 62nd.

Most of these statistics suggest that Canada’s athletes should have won more medals and that there’s room for improving policies for training and selecting future Olympic teams.

How this can be done is revealed by considering countries’ ranking by the per cent of team members who have won a medal. The table below shows that only 12 per cent Canada’s team had won a medal, bringing Canada a 53rd place. The U.S. team ranks second with 53 per cent of its team having won a medal. This success is likely due mainly to the competitive sports programs of American colleges and universities, which train athletes and offer a large pool of talent from which to select the best for the Olympic Games.

Rank | Country | Weighted | Size of Team | Ratio of |

Medals Won | Team Size/Medals | |||

2 | United States | 296 | 554 | 53 |

6 | Jamaica | 32 | 68 | 47 |

7 | Great Britain | 171 | 366 | 46 |

9 | Kenya | 37 | 89 | 41 |

35 | New Zealand | 39 | 199 | 19 |

44 | Australia | 64 | 421 | 15 |

53 | Canada | 37 | 314 | 12 |

Jamaica and Kenya are ranked in sixth and ninth place, respectively. The two countries’ small teams competed successfully in sprints and endurance races mainly because they focused on a small number of sports in which they competed. Great Britain’s medal haul was its largest 100 years. Its success was partly based on rich financial support from the government’s National Lottery that had risen to record levels in the run-up to the London Olympics. But the success was also due to its strategy of focusing its financial support on a strictly limited number of sports with past success in international competition.

Canada, New Zealand and Australia have very similar histories, cultures and per capita incomes. New Zealand’s population is 4.5 million, Australia’s 24 million and Canada’s 36 million. These figures suggest that Canada should have outperformed the other two countries. In fact, it ranks the lowest among the three in 53rd place while New Zealand and Australia are in 35th and 44th place, respectively.

Although the comparison of Canada with Australia and New Zealand neglects the countries’ different climates and the greater attention Canada pays to Winter Olympics, the other Canadian statistics (see chart below) suggest that Canada’s policies for the training and selection of athletes for Olympic competition could be improved.

Thus, Canada might encourage more competition among institutions of higher learning and integration of sports programs with U.S. academic leagues. Of course, more financial support from the government and private sector would always help. But whatever the level of such financial support, a more determined focus on a limited range of sports, athletes and trainers with past success in international competition could increase future Olympic medal counts.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.