Canada’s real environmental record (not what some would have you think)

“Canada gets a D grade on environmental report card,” blares a headline at the Weather Channel. A CBC article carries the headline “Canada ranked 14th out of 16 on protecting the environment, Conference Board says.” Business Vancouver tells us, “B.C. gets a ‘C’ on its environmental report card, Conference Board.”

Now, being with the Fraser Institute, I’m all about measurement and report cards. We do a lot of such things ourselves. The problem is that these headlines run counter to the vast majority of what the data tell us about Canada’s environmental track record. In fact, the data show that the air and water we all use are getting cleaner—not more polluted. The disconnect between these facts and the findings of the recent report card cause one to wonder what exactly the Conference Board is measuring—it certainly isn’t what most people think of as environmental.

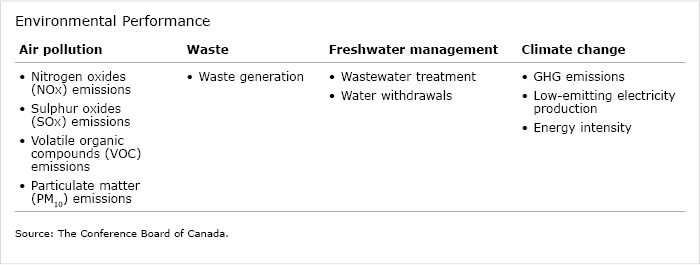

Let’s consider the Conference Board’s “environmental” metrics:

We’ll start with air pollution. As we documented in the study Canadian Environmental indicators—Air Quality, in most instances, Canadians currently experience significantly better air quality than at any other time since continuous monitoring of air quality began in the 1970s. Most notably, concentrations of two of the air pollutants of greatest concern—ground-level ozone and ultrafine particulate matter—have generally decreased across Canada since 2000. By focusing on per-capita emissions, the Conference Board turns a great air pollution control story upside down. Of course Canadians are likely to emit more per capita—we live in a huge, cold-weather climate with vast transportation needs, and we service a massive economy to our south with goods and services, including natural resources.

What’s important about air quality is not absolute emissions per capita, but whether people and the environment are being harmed by air pollution. On that front, the answer is “very few.” Air quality in Canada rarely crosses the thresholds that indicate a significant health risk exists. And those thresholds, one should add, are themselves highly conservative. Canadians need have little concern that it’s a dangerous act to breathe.

Now, let’s move onto waste generation. First, it’s unclear how a metric of waste generation tells us anything about environmental harm—that would all depend on how waste is disposed of, not how much one makes. But Canadians are hardly lackadaisical about waste minimization and diversion. According to Statistics Canada, 92 per cent of households in Canada have access to recycling programs, and 98 per cent of those households actively recycle: 94 per cent recycle glass, 97 per cent recycle paper and plastic, and 92 per cent recycle metallic waste.

The same is true for water withdrawals and wastewater treatment—what matters is not how much we take out of the environment, it’s whether those withdrawals actually damage surface water and ground water that matters. On that score, Canada’s doing just fine. Our recent study on water quality showed amazing progress in Canada when it comes to cleaning up our waterways and keeping withdrawals to ecologically safe levels.

Finally, about those greenhouse gases. As Environment Canada points out, Canada’s greenhouse gas levels have been declining since 2005 on a total-mass basis, on a per capita basis, and on the basis of emissions per unit of economic productivity. By any measure, Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions are in decline.

Slamming Canada based on an index that looks at indicators tangential to actual environmental and human health impacts while ignoring the massive progress Canadians have made in cleaning up and protecting their environment will not further the cause of environmental and health protection. To the extent that it’s used to bludgeon Canadian governments into emulating Ontario’s green power fiasco (where high energy prices constitute a monthly mugging for Ontario’s poorer citizens), the Conference Board report card is likely to lead to reduced economic productivity for both the private and public sectors, sapping the very revenues needed to measure environmental progress, and deal with environmental problems that the private sector can’t, or won’t.

That’s not to suggest that Canada is free of environmental challenges—it certainly isn’t, Canada is a natural resource powerhouse that has always faced, and will always face, numerous environmental challenges. But an objective view of Canada’s environmental performance hardly justifies slamming the country as some kind of environmental laggard and international lay-about, as the Conference Board would have us believe.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.