As the world shifted to free markets, poverty rates plummeted

This year’s Economic Freedom of the World Report showed the astonishing growth of free markets and globalization back to 1950—and what a time it has been.

The report, based on 2016 data, the most recent available, measures the extent of free markets in 162 jurisdictions globally, spotlighting their openness to trade and thus globalization. The report scores policy on a scale of 0 to 10. Higher scores indicate freer markets.

The extent and depth of free markets has grown dramatically since 1950. The average global score increased from 5.2 in 1980 to 6.7 in 2000 and has remained relatively stable since. Prior to 1980, data are not available for enough jurisdictions to estimate global averages but individual countries, both developed and undeveloped, show remarkable gains since the 1950s.

Canada for instance scored 6.5 in 1950 and was 3rd in the world. By 2016, Canada’s score had soared to 8.0 but its rank fell to 10th as other countries moved even faster. Ireland rose from 5.8 in 1950 to 8.1 in 2016, New Zealand from 5.9 to 8.5, Norway from 6.1 to 7.6, Denmark from 5.8 to 7.8, Peru from 4.1 to 7.4, and Taiwan from 4.4 to 7.9. While Taiwan’s and Peru’s increases were exceptional, the other examples are typical.

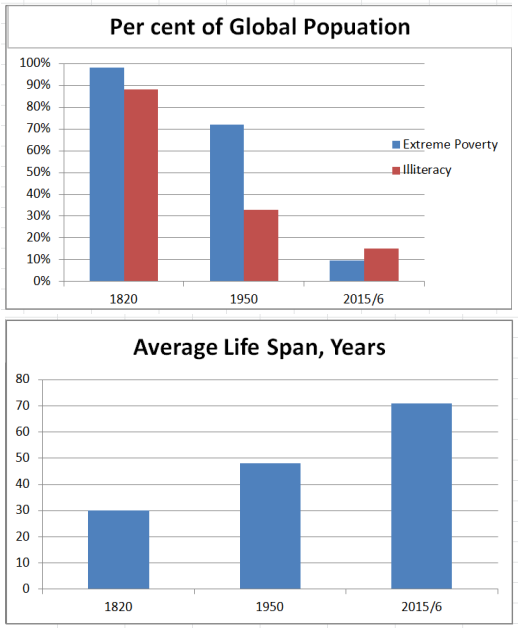

Yet, as the world shifted to free markets, opponents warned (and continue to warn) of dire poverty, falling educational standards and disease, as free markets take hold. These claims have as much reality as harpies and Minotaurs. In 1950, as free markets began their post-Second World War surge, the world’s population was 2.52 billion. More than 70 per cent, 1.81 billion, lived in extreme poverty, less than US$1.90 a day (purchasing power parity adjusted US$).

You might think massive population growth since 1950 would expand poverty, but that misunderstands free market dynamism. By 2015 (the most recent global poverty estimate), world population had exploded to 7.35 billion yet only 0.7 billion lived in poverty, less than 10 per cent albeit still too many. Despite a three-fold increase in global population, the absolute number of people living in poverty dropped by more than 60 per cent.

Similar trajectories hold for other indicators of well-being. During the age of globalization, 1950-2016, illiteracy fell from two-thirds of the population to 15 per cent. Average life spans increased from 48 to 71 years. Progress was not caused by the passage of time, but rather by gains in freedom. The bad old days live on in countries that reject free markets and economically enslave their people.

Today, in the economically freest countries, the top quarter, only 1.5 per cent of the population live in extreme poverty and 4.3 per cent in moderate ($3.20 a day) poverty compared to 51.7 per cent in extreme poverty and 31.7 per cent in moderate poverty in the quarter least-free countries.

Life expectancy is 80 years in the freest countries compared to 64 in the least-free countries. Average per capita income in the freest countries is $40,376 compared to $5,649 in the least-free countries.

Literacy is 95.1 per cent among men and 94.1 per cent among women in the freest countries but only 74.7 per cent and 59.7 per cent respectively in the least-free countries, with such outcome gaps between men and women typical in un-free countries.

Nor is this a case of some countries inheriting prosperity. Once very poor places such as Singapore, Taiwan and Botswana, or relatively poor places such as Ireland, experienced massive increases in prosperity and decreases in poverty when they embraced economic freedom.

The changes are even starker if traced back to the time when the evolution of modern free markets began, arguably around 1820. Average life span then was about 30 years, only 12 per cent of the world’s population was literate, and more than 98 per cent of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty.

Today, with populist and anti-market groups attacking the very foundation of the economic system that created unprecedented well-being, the economic freedom index provides a measure of the growth of free markets to see what has been accomplished.

We are living in a time where humans have more prosperity, less poverty, better health and greater education than at any time in human history—not by a little but by a lot. Let’s hope we don’t blow it.