Why Rice plays Texas, the moon shot and a very big public good

Of all the great lines John F. Kennedy and his speech writer and alter ego, Ted Sorensen, crafted during the 1950s and ’60s, one of my favourite is Kennedy’s throwaway quip in 1962: “Why does Rice play Texas?,” which he jotted onto a text drafted by Sorensen and then delivered like an experienced comedian—I’ll explain the joke in a minute—in one of his most consequential and eloquent speeches of all.

Context obviously matters. The occasion was a speech at Rice University in Houston, Texas, on September 12, 1962. The subject was the United States space program and its then year-old goal of putting a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s. Houston was the obvious place for the speech because, with Vice-President Lyndon Johnson hailing from Texas and heading the administration’s Space Council, that city had just been made the control centre for NASA’s manned space flight operations, following a 23-city competition.

Rice University was and is the premier university in Texas and it was to be associated with the new space centre, which was built on land that had been ceded to Rice. The University of Texas was also and is a great university but it was and may yet be best known for its football team. Its Longhorns have won the national collegiate championship four times. Rice’s Owls (yes, Owls) have never won the national championship. Since the two universities’ first football game in 1914, the Longhorns lifetime record against the Owls is 72-21-1. Five weeks after Kennedy spoke, on the very gridiron he spoke from, Rice actually tied Texas. Since then it has beaten Texas but twice, in 1965 and 1994.

OK, enough football history. Why are we talking about Rice vs. Texas? It comes up in the peroration of Kennedy’s speech that day in 1962:

But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas?

We choose to go to the Moon… We choose to go to the Moon… We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win…

Some clips of the speech edit out “Why does Rice play Texas?” You’re then left wondering why Kennedy keeps repeating “We choose to go to the Moon…” He keeps repeating it because his Rice audience is still laughing at his football joke.

I can see why people do edit it out. Without the context—which it took me three paragraphs to explain—it doesn’t make sense. And you don’t really want to explain it. As maybe I’ve just proved, the best way to kill a joke is to explain it.

But the joke’s omission is unfortunate. To my kind, it says a lot about both the era and the enterprise. Sure, it was an important, historic mission and lots of people were completely earnest about it—as they have been completely earnest in remembering it these last few weeks. But part of having the right stuff, which the Apollo astronauts had just as much as the Mercury ones, was not taking yourself too seriously. Yes, we’ll risk our lives but we’re not going to get all solemn about it. It was a mid-century ethos that seems to have been especially strong among Second World War veterans, which of course Kennedy was. The right stuff also meant understanding that some things were worth trying even if success was not guaranteed, and with the moon shot it certainly wasn’t. Kennedy’s speech goes on to describe what’s involved in getting to the moon and back, including building a rocket with metal alloys that hadn’t been invented yet. Even in retrospect, it’s a daunting to-do list.

Lots of economists I’ve run across, like many people who began life as nerds, are and were big fans of the space program and the moon shot. Some economists try to do an ex post cost-benefit analysis, arguing that there were lots of big spillovers in terms of computing power, metallurgy, miniaturization and yes, Velcro and instant orange juice powder. But in the late 1950s and early 1960s no one was saying we should go to the moon because a peacetime Manhattan project would produce lots of neat new consumer products.

No, what they were saying was that we had to go to the moon because if we didn’t the Soviet Union would and we simply could not abide that. The big motivation was to demonstrate that our social system was better than theirs, that free men operating in a creative free enterprise system could get a seemingly impossible job done on time and… well, not exactly under budget. The great irony, of course, was that the superiority of capitalism was going to be demonstrated by a large government project, financed by Congress and directed by a government agency, albeit one that contracted out most of the hard jobs to private aerospace companies.

Fifty years later the private sector is very active both on the contracting side but also in thinking up, initiating and financing space projects. Are there many technologies more impressive than Elon Musk’s Falcon rockets guiding themselves back to Earth to land (most of the time softly) on a barge? But in 1961, if it was going to be done it was going to have to be done by government and not just any government but the U.S. government.

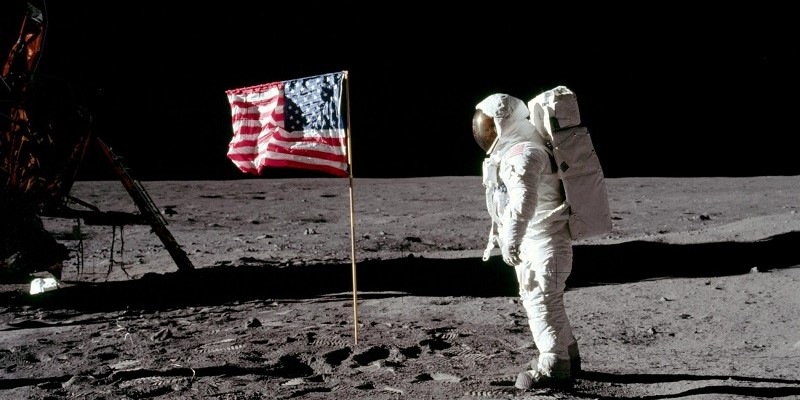

The moon project was very much a public good. Use of the term “good” does not mean it was necessarily a net positive. There are such things as public bads (think harmful atmospheric change). And at the time there were lots of people who thought all the money spent ($153 billion in 2019 dollars) was a waste. No, the term “public good” simply means there were lots of beneficiaries (including a 50-year younger version of myself) who did benefit, who couldn’t be prevented from benefiting, but who didn’t help with the finance. How did we benefit? The astronauts left a plaque saying “We came in peace for all mankind.”

That was obviously political. But they did go for all of us. All of us watched. It was wonderful entertainment, a decade-long adventure that was televised extensively—the most compelling reality TV ever, even if most of us saw it in black-and-white. We all sat on the edges of our seats, holding our breath. We all pondered the achievement itself and the new perspectives it gave us, the sense of large possibilities, if people turned their minds to things. That did lead to some ultimately erroneous thinking—if we can put a man on the moon, why can’t we end poverty? One’s a difficult but relatively straightforward engineering problem. The other involves behaviour, incentives and institutions that are very hard to re-engineer.

But it was a very big public thing. And given the ability to at least try it, it would have been a shame not to have done. Whether for individuals or countries, hard things are good tests. Rice does still play Texas.