Interest on federal debt—a growing problem

The Trudeau government will table its 2021 budget next week. After the prime minister committed to “absolutely” balance the budget again in the near future, it will be particularly important to see the details of when and how the government plans to achieve this objective.

In its fall economic statement, the government projected it will run a deficit of $381.6 billion in 2020/21, which is equivalent to approximately 17.5 per cent of the economy and by far the largest federal deficit since the Second World War.

Balancing the budget again will not be easy. Bringing spending in line with revenues will be important, but the challenge is exacerbated by federal debt interest payments. Indeed, although interest rates are at historic lows today, potential rising interest rates in coming years could increase interest costs and make the task more difficult.

Consider this. Interest payments on the federal debt are expected to equal $20.2 billion in 2020/21. That amount has declined compared to recent years but is by no means insignificant. Indeed, Ottawa currently spends roughly the same amount on interest payments as it does on the equalization program.

According to last fall’s federal economic statement, debt interest payments will continue to grow over the next five years. By 2025/26, debt interest costs will reach a projected $34.3 billion and consume a larger chunk of federal government revenue than it does today. In fact, interest payments are expected to exceed the amount of the forecasted deficit ($24.9 billion) for that fiscal year. Put differently, the government would actually run a surplus rather than a deficit in 2025/26, if not for debt interest.

If we examine Canada’s past experience with federal debt interest, we also observe the extent servicing the debt makes it harder for government to balance its books. Public finance economists use the term “primary surplus or deficit” to describe what a government’s fiscal balance would be in the absence of debt interest. A government is said to incur a “primary surplus” when current revenues exceed program spending and a “primary deficit” when the opposite is true.

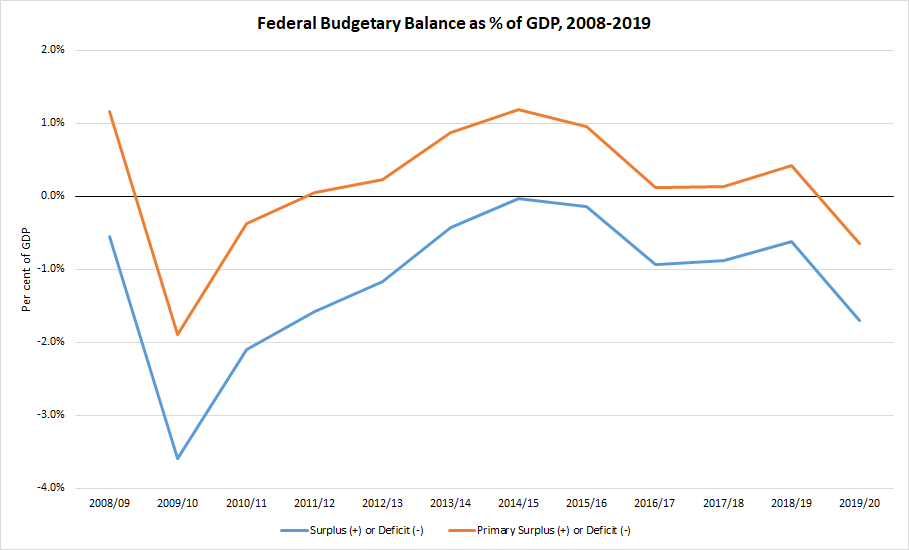

The federal government ran 12 consecutive budget deficits between 2008 and 2019. However, as the figure below demonstrates, Canada actually ran a “primary surplus” in nine of these years and a “primary deficit” for just three years.

This chart is not meant to discount the scale of those deficits but rather to illustrate the negative impact debt interest payments can have on fiscal balance over time. Adding more debt—and paying the resulting interest—creates a vicious circle for future governments by contributing to even more deficits, debt and interest payments in later years.

Moreover, a big contributor to debt accumulation in recent years has been the growth in federal government program spending. For instance, nominal program spending increased by 27.6 per cent between 2015/16 and 2019/20 whereas total revenues only grew by 14.2 per cent. Simply put, Ottawa has consistently incurred deficits because it borrows to finance current spending and pays the resulting interest payments for years afterwards.

Returning to balanced budgets, therefore, will require a disciplined approach to constrain the growth in debt interest. The prospect of rising interest rates would increase the difficulty of this challenge, but putting off the tough decisions will only add to the pain later. Developing a plan to halt debt accumulation by reducing spending will save Canadians money on interest payments and ensure federal finances are sustainable for future governments.