Age of eligibility for government retirement programs—Canada remains an outlier

In most high-income countries including Canada, populations are aging. This demographic reality is putting pressure on government finances, which will grow in the years ahead. All else equal, an older population means higher health-care costs and more spending on income support for retirees. Meanwhile, there will be a negative effect on tax revenue due to the presence of fewer working-age people.

Many countries around the world are responding to these financial pressures by increasing their ages of eligibility for government retirement programs. This is a prudent response to the demographic pressures described above. Relatedly, people are living longer. Of course, this is great news. However, refusing to increase the retirement age as people live longer lives generally increases the cost of retirement programs as more people are eligible for them for a longer period of time. Raising the age of eligibility can help restrain cost growth.

A recent Fraser Institute study examined developments in 23 high-income OECD countries (including Canada) to assess policy trends with the age of eligibility for government retirement programs. At present, eligibility for Canada’s Old Age Security (OAS) and GIS (Guaranteed Income Supplement) is 65 years old.

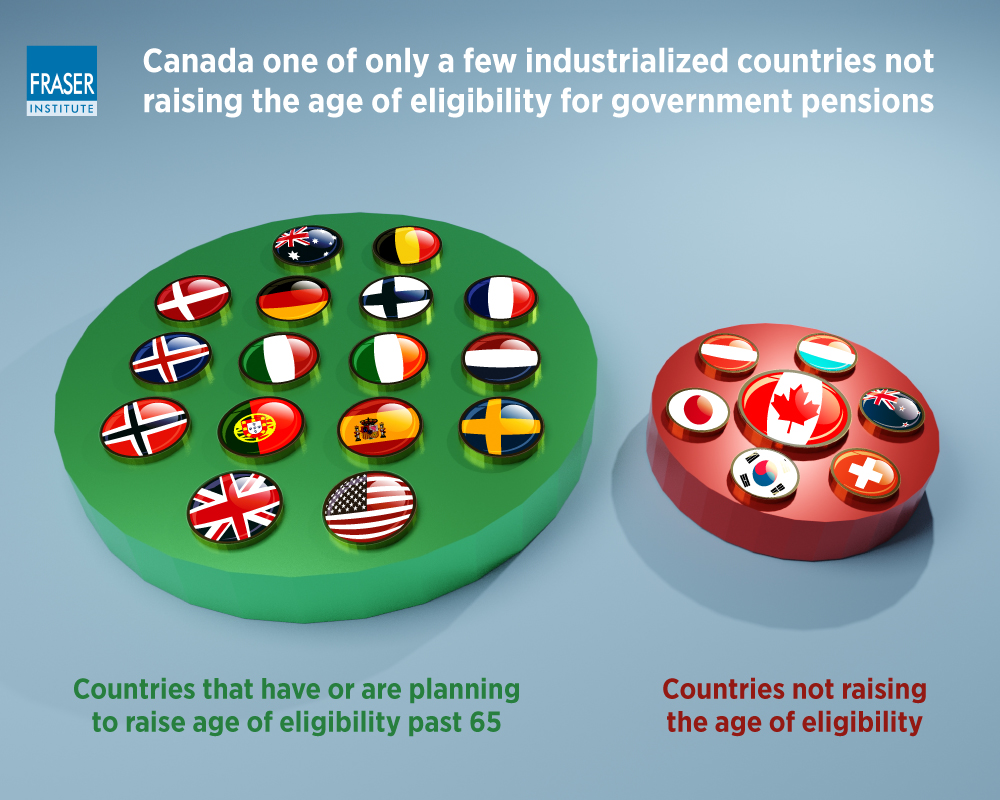

The results were striking. Of the 23 examined, 16 countries have either already increased the age of eligibility for public retirement programs to above age 65 or are in the process of doing so. Five countries are indexing their age of eligibility for their primary retirement programs to life expectancy, meaning the retirement age will automatically adjust upward as life expectancy increases. In sum, there’s a clear trend across high-income countries towards increasing the age of eligibility.

However, Canada is not participating in this international trend and is maintaining its eligibility age at 65 years old. As a result, once all of the currently planned reforms are fully implemented, Canada’s age of eligibility for government retirement programs will have one of the lowest age of eligibility of the 22 high income OECD countries we analyzed. Only six other countries are not in the process of pushing their retirement ages above age 65.

The absence of reform in Canada is particularly interesting given that in 2015, the Trudeau government reversed a 2012 reform that would have increased the age of eligibility for OAS and the GIS supplement to 67 years old by 2029. In other words, Canada was on course to participate in the international cost-restraining trend of raising the age of eligibility but then reverted to the status quo of 65.

Around the world, governments in high-income countries are responding to aging populations and longer life expectancies by raising the age of eligibility for public pensions and other retirement programs. Canada’s decision to not take similar steps will put additional long-term pressure on our government finances.