Another broken promise—federal government ditches latest fiscal pledge

It’s hard to keep track of all the federal government’s broken promises on deficits and debt. And that’s a problem. Fiscal credibility is important, not only for the country’s finances, but for potential investors and entrepreneurs who are considering whether or not Canada is a good place to do business.

While last week’s federal budget confirmed the government’s latest fiscal promise will be broken, let’s first start with the Liberal 2015 election platform, which promised “modest short-term deficits of less than $10 billion in each of the next two fiscal years” and to “return Canada to a balanced budget in 2019/20.”

These promises, of course, barely outlived the campaign. Within months of being elected, the Trudeau government backed away from both commitments.

By the time of its first budget in early 2016, the government abandoned entirely its commitment to balance the budget, presenting substantial deficits through to 2020/21—a year after its first mandate ends. In some years, the projected deficits tripled the amount promised in the Liberal platform.

Once it became clear that the government had no intention of balancing the budget during its mandate, it quickly created new fiscal targets centered on the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio. This is an important metric that measures the burden of a government’s debt relative to the resources available in the economy to sustain that debt. But even after pivoting to this metric, the government has repeatedly moved the goalposts and broken several promises.

Initially, the government promised to “reduce Canada’s federal debt-to-GDP ratio each year.” After the election in late 2015, Finance Minister Bill Morneau repeatedly pointed to annual reductions as a “fiscal anchor” that would prevent rapid deterioration in Ottawa’s fiscal position. At the same time, the prime minister promised to reduce the ratio “every single year” because “that’s what’s important for the fiscal health of our country.”

Yet the government failed to deliver on this pledge. Just months after the above pronouncements, the 2016 budget showed the debt-to-GDP ratio would tick up in 2016/17 from the previous year’s level.

After breaking that promise, the government made another promise, that: “By the end of our first mandate, Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio will be lower than it is today.”

Fast forward to last week’s 2017 budget. According to the government’s own projections, this latest promise won’t be kept either.

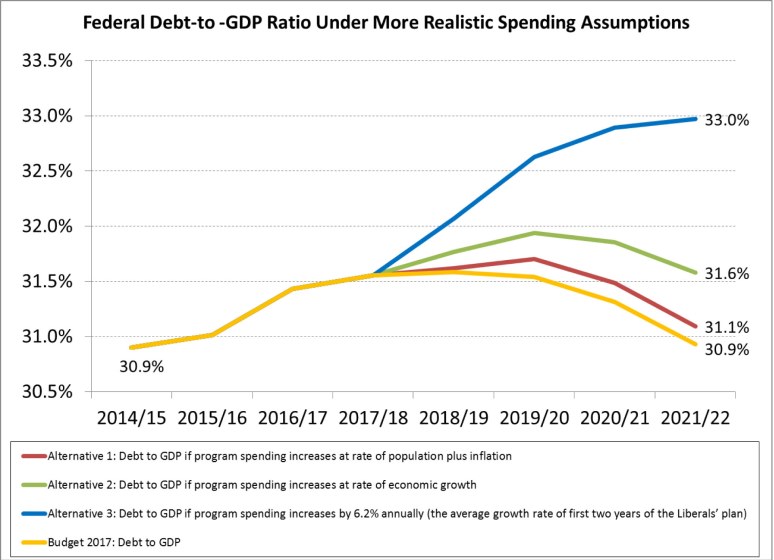

Why? Because in 2014/15, the year before the government was elected, the ratio stood at 30.9 per cent. By 2019/20, the last year of its current mandate, the 2017 budget forecasts the debt-to-GDP ratio will be 31.5 per cent. So contrary to the government’s latest promise, the ratio is not going down over its mandate—it’s going up.

And crucially, there are a number of reasons why the debt-to-GDP ratio may be higher than the government now projects. For one thing, the projections are based on questionable assumptions about Ottawa dramatically slowing the rate of spending growth in the future.

Starting in 2018/19, the budget plans to reduce inflation adjusted per-person spending, which would be a marked departure from the government’s track record. There’s no plan for how exactly such spending restraint will be delivered. And equally important, it contradicts the government’s own rhetoric about how more spending will help grow the economy.

In fact, using assumptions about future spending that more closely align with the government’s track record to date, Ottawa may add up to another $122 billion in debt over what it’s currently projecting from 2018/19 to 2021/22. That would cause the debt-to-GDP ratio to rise further still, potentially reaching 33.0 per cent by 2021/22 (see accompanying chart).

Importantly, these revised debt projections do not account for other risks that could cause the debt to climb even higher including lower-than-expected economic growth and higher-than-expected interest rates.

Less than two years into the government’s mandate, it’s increasingly worrying the number of times it has discarded its fiscal anchor when the discipline it is meant to impose becomes inconvenient. With the unceremonious discarding of the debt-to-GDP promise, it’s clear that federal fiscal policy is being set without any fiscal anchor at all.

Authors:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.