It has been more than two years since an independent commission submitted its report to the Ontario government on the provinces poor public finances and high government debt.

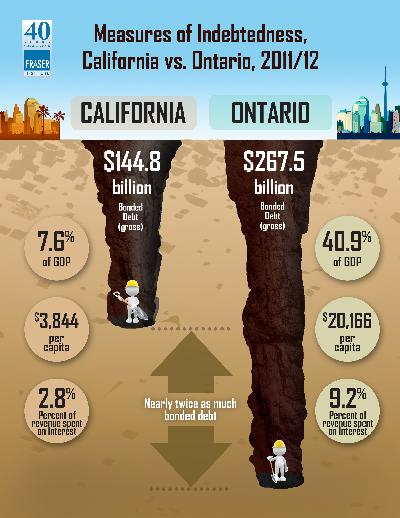

government debt

On February 18th British Columbians will be watching to see if finance minister Mike de Jongs budget sets out a plan to deliver on his governments ambitious goals with respect to economic growth and job creation. And the truth is, the province needs it. The past year was a disappointing one for BC in terms of economic and employment growth compared to other provinces.

With the holiday season now behind us, the oncoming flood of credit statements to Canadian households is a powerful reminder that there are no free lunches. Borrowing to pay for current consumption brings interest payments, and ultimately, the need to pay off principal balances. Most Canadians are intimately familiar with this reality when it comes to their household finances. But this same reality also applies to governments. As taxpayers, Canadian families are also responsible for interest on government debt. And these payments are significant.

The government should fix it is a common refrain when people encounter a problem in society. Governments happily oblige because it means more votes for politicians and more work for bureaucrats. Governments themselves also undertake a number of things from encouraging Canadians to be more active, to propping up domestic industries, to trying to create jobs. But can government really deliver? Evidence suggests the answer is a resounding no.

Over the course of the past several months, outgoing Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney and Federal Finance Minister Jim Flaherty have repeatedly warned that Canadians are spending beyond their means and taking on too much debt.

A concern of the Bank of Canada...has been the pace of growth of household debt Carney recently noted. Minister Flaherty added, While interest rates are currently low by historical standards, eventually they will rise. Canadians should . understand this when taking on significant debt

You might think the federal Conservatives, who added $125-billion to the federal debt since 2008 and will add another $21-billion by the end of March, might be shy about unnecessary expenditures. Alas, thats not the case, as it appears Prime Minister Stephen Harper and his colleagues would rather hand out cash to corporate Canada instead.

In just the first two weeks of January, the prime minister announced another $250-million for the Automotive Innovation Funda federal subsidy program that provides the auto sector with taxpayer cash for research and development.

When Canadas premiers recently met in Halifax, talks of a possible pipeline to move oil from Alberta to eastern Canada dominated national headlines. There was also mention of talks about trade, immigration, skills training, and infrastructure. One issue that didnt receive nearly as much attention is the management of public finances and growing government debt.

While some economists take great satisfaction when their forecasts come true, I am not in that camp.

As Terence Corcoran noted on this page Wednesday (On track for more deficits), for the past several years my colleagues and I have warned that the federal government's plan to balance the budget has been based on risky projections - optimistic forecasts of revenue growth (averaging 5.6% per year) and unrealistic plans for spending restraint (average increases of just 2.0% per year).

There it was on the front page of The Globe and Mail: $5.2-billion [in] total spending cuts. The Toronto Star screamed: Tories slash spending in fiscal overhaul, while CTV proclaimed: Budget to cut spending nearly $6-billion.

Perhaps they read a different budget than the one we found on the Department of Finance's website. Here's what the Conservatives' budget actually stated: The results of the government's review of departmental spending amount to roughly $5.2-billion in ongoing savings.

That's savings, folks, not cuts.